According to a currrent article in The Atlantic, “if Jefferson became president, thundered a Federalist opponent in 1798, ‘the Bible would be cast into a bonfire, our holy worship changed into a dance of Jacobin phrensy, our wives and daughters dishonored, and our sons converted into the disciples of Voltaire and the dragoons of Marat.’ Two years later, as news of Jefferson’s election victory spread, there were reports that pious housewives in New England were burying their family Bibles for protection, or hiding them down wells.”1

It seems a bit ridiculous, looking back. Certainly, Thomas Jefferson was no modern evangelical. Raised in the Anglican church, however, he did seem to cling to a belief in a higher power.

Which? Atheist, infidel, heretic?

Church historian Bruce Gourley notes that “Charles B. Sanford’s The Religious Life of Thomas Jefferson (1984) provides lengthy evidence from many contemporaries of Jefferson. He references the hundred or so pamphlets and newspapers that accused Jefferson of being an atheist, infidel and/or heretic, as well as numerous sermons declaring that if elected, Jefferson would ruin religion, overthrow Christianity, and ban the Bible from the United States. Conservative Christians considered him thus throughout his life. Long after his presidential tenure, in 1830, the Philadelphia public library refused to include books about Jefferson on its shelves because he was considered an infidel and heretic.”2

In the summer of 1998, the Library of Congress hosted an exhibition on “Religion and the Founding of the American Republic” that included a letter that Jefferson wrote to a group of Baptists. The following comes from an article on the LOC website about that exhibit.

A wall of separation

“Thomas Jefferson’s reply on Jan. 1, 1802, to an address from the Danbury (Conn.) Baptist Association, congratulating him upon his election as president, contains a phrase that is as familiar in today’s political and judicial circles as the lyrics of a hit tune: ‘a wall of separation between church and state.’ … During the presidential campaign of 1800, Jefferson had suffered in silence the relentless and deeply offensive Federalist charges that he was an atheist. Now he decided to strike back, using the most serviceable weapon at hand, the address of the Danbury Baptists. …

“The unedited draft of the Danbury Baptist letter makes it clear why Jefferson drafted it: He wanted his political partisans to know that he opposed proclaiming fasts and thanksgivings, not because he was irreligious, but because he refused to continue a British practice that was an offense to republicanism.”

Not so fast, Tom

After consulting with two political allies, Jefferson decided to delete the references to fasts and thanksgivings. The words would be off-putting to Northern Republicans who liked this religious ritual in spite of its tie to the British ways of governing. Jefferson needed to remain in their favor. He scratched those lines out.

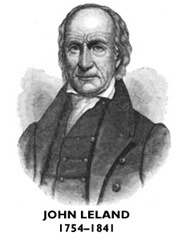

“Withholding from the public the rationale for his policy on thanksgivings and fasts did not solve Jefferson’s problem, for his refusal to proclaim them would not escape the attention of the Federalists and would create a continuing vulnerability to accusations of irreligion. Jefferson found a solution to this problem even as he wrestled with the wording of the Danbury Baptist letter, a solution in the person of the famous Baptist preacher John Leland, who appeared at the White House on Jan. 1, 1802, to give the president a mammoth, 1,235-pound cheese, produced by Leland’s parishioners in Cheshire, Mass.

Baptists in the House

“One of the nation’s best known advocates of religious liberty, Leland had accepted an invitation to preach in the House of Representatives on Sunday, Jan. 3, and Jefferson evidently concluded that, if Leland found nothing objectionable about officiating at worship on public property, he could not be criticized for attending a service at which his friend was preaching. Consequently, ‘contrary to all former practice,’ Jefferson appeared at church services in the House on Sunday, Jan. 3, two days after recommending in his reply to the Danbury Baptists ‘a wall of separation between church and state’; during the remainder of his two administrations he attended these services ‘constantly.’

“[G]oing to church solved Jefferson’s public relations problems, for he correctly anticipated that his participation in public worship would be reported in newspapers throughout the country. A Philadelphia newspaper, for example, informed its readers on Jan. 23, 1802, that ‘Mr. Jefferson has been seen at church, and has assisted in singing the hundredth psalm.’ In presenting Jefferson to the nation as a churchgoer, this publicity offset whatever negative impressions might be created by his refusal to proclaim thanksgiving and fasts and prevented the erosion of his political base in God-fearing areas like New England.

Faithful more than political?

“Jefferson’s public support for religion appears, however, to have been more than a cynical political gesture. Scholars have recently argued that in the 1790s Jefferson developed a more favorable view of Christianity that led him to endorse the position of his fellow Founders that religion was necessary for the welfare of a republican government, that it was, as Washington proclaimed in his Farewell Address, indispensable for the happiness and prosperity of the people. Jefferson had, in fact, said as much in his First Inaugural Address. His attendance at church services in the House was, then, his way of offering symbolic support for religious faith and for its beneficent role in republican government.”3

Bible believers in November 2020

We cannot know the hearts of prior presidents nor of current candidates. What we can do is be wary of extremists’ talking points that seek to diminish the humanity of a candidate, including their spirituality. What we can do is pray for them, that they will follow the Light that they have been given and that they will be granted more Light. What we can do, personally in a politically charged season, is read and follow the truths of the Gospel message which is focused on love, justice, and mercy.

What we need not do is bury our Bible.

- https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/11/peter-manseau-jefferson-bible/616476/ [↩]

- http://www.brucegourley.com/baptists/thomasjeffersonatheist.htm [↩]

- https://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/9806/danbury.html [↩]