It is startling to realize that no document from the early church explains how the Bible came to be. At some time, someone determined the criteria for the selection of writings for the canon of Christianity. It seems like that would be a big enough deal that there would be historical documentation. But, there’s not.

Well, not exactly. There is documentation that requires one to read between the lines. For example, there are letters from one church leader to another noting what books their congregation considers to be scripture. From these lists, we can see the evolution of the canon. The most complete New Testament list that we have that is comparable to what is found in most Protestant English Bibles is found in the Easter letter of 367 AD from the Church Father, Athanasius of Alexandria.

Some of the world’s best Bible scholars and historians have dedicated their careers to the research of the canon’s evolution. They work as holy detectives sifting through ancient manuscripts, judging the character and motivations of witnesses, and finally drawing conclusions that will always remain theory.

Five probable criteria

Lee McDonald is one of the best of these educated guessers. The author of many books about the formation of the canon, he offers five criteria for books that “made the cut.” In my interview with Dr. McDonald, he says,

“There is no text in antiquity that tells us how the Bible was formed – none. What we do is draw inferences from what the church fathers say and how things were practiced in the churches.

- The first thing we can say, if it was believed that an apostle wrote it, then, of course, it was in….

- The second [criteria] was orthodoxy. There were the core traditions that were circulating in the early church that we call the orthodox traditions -Christ died for our sins, was buried, and raised again, and so on. If they cohered with that, they got in. They were rejected if they didn’t….

- The third is wide-spread use…the books that were widely read and circulating in their communities…

- A fourth one is antiquity. The Muratorian fragment, which I think [was written in the] late fourth century, speaks about the Shepherd of Hermas shouldn’t be read publicly but it could be read and should be read privately because it was written ‘in our times’ not in the earlier apostolic times….

- Another [criteria] is called adaptability. Was a text that was written able to continue in the churches and show relevance to their own circumstances?”

All of which is to say that your favorite poet, preacher, or pundit’s work will always be ineligible as a latecomer to the canon. As inspirational as it may be, Footprints in the Sand will never set foot in the canon. The canon is closed unless, theoretically, an authentic apostle’s writing is discovered that is orthodox, becomes read universally, and is relevant to modern churches and Christians.

What’s in Your Canon?

Of course, there is a sense in which we each have our own canon of scripture. We are selective in which parts of the Bible are the most inspirational, helpful, and relevant. Passages that are obscure, confusing, or a bit too challenging don’t get much of our attention.

Thus, our canon is created in our image. We select the passages that affirm our image of God, our sense of ethics, and our comfort level of behavior. We select the passages that make us feel good about God’s care, provision, and ultimate victory.

What amazes me about books that “made the cut” into the Old and New Testaments is that they contain passages that make us moderns uncomfortable. Maybe the ancients were not all that comfortable with those passages and books, either – yet they kept reading them, kept pondering them, and kept them preserved for future spiritual pilgrims.

There are passages that deal with real life, real emotions, real tensions with God that I would have probably edited out, had I the opportunity. What if someone reads the rants of Job and loses their faith? What if someone reads Jesus’ cry from the cross, “My God, why have you forsaken me?” and begins thinking that God could ever forsake us? What if someone reads all those Psalms, which are laments with challenges to God’s neglect of God’s people and accusations of God breaking God’s promises and the worries that God is not quite up to being, well, God?

Being more picky

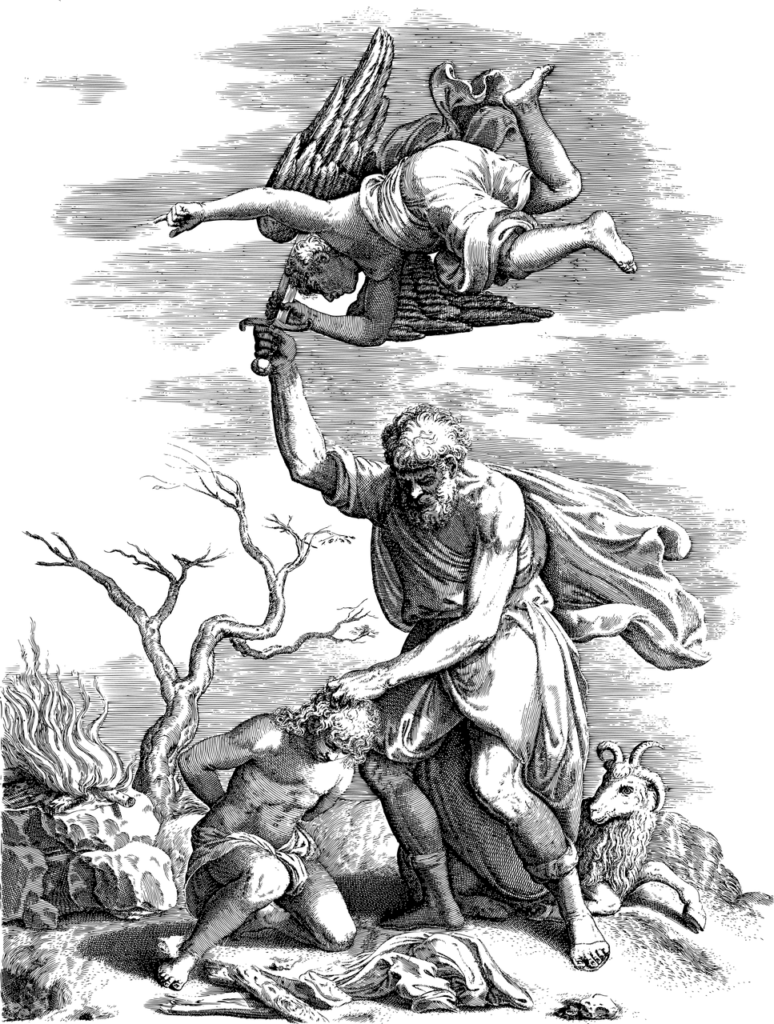

I think I would have been more selective. Were we to re-examine the books of the canon in order to establish a new one, much of the current Bible would require surgery. Abraham’s (attempted) sacrifice of Isaac, Jesus’ teaching on divorce, the genocidal acts of God’s people in Joshua, Paul’s teaching related to slavery, that weird last book of the Bible -we can do without those passages in our enlightened day, can’t we? Let’s clean up those stories about our heroes and their faults – Moses’ anger, Abraham’s manipulations, David’s adultery, the disciples’ overall denseness.

Maybe in God’s Providence, there is a reason the canon is closed. In our attempt to be more comfortable, we would be less honest about what it means to be holy and what it means to be human. Maybe this is why the Church (in ways still unclear to us) ultimately said, “no more and no less than these. Deal with it.”

Thank you for sending this to me. Much appreciated. I will pass it along to others and hopefully they will join your podcasts. —Lee

Many thanks for this helpful blog, Rick. As necessary as McDonald’s careful reconstruction of the canonical process is (and others like his), it remains severely gapped for lack of artifacts of the kind historians like McDonald require. This is–at least to me–deeply unsatisfying. What I think must be added to these historical explanations is a theological one, not only anchored by divine providence (so John Webster) but primarily by a pneumatology of scripture that follows the Spirit’s agency from composition to canonization to scripture’s ongoing reception as God’s word for God’s people. A robust understanding of God’s hallowing of select texts that the church then recognizes in the fulness of time as its scripture is a way forward in this discussion. Unfortunately, the modern academy, filtering down to the local parishes, have divided biblical studies (and its various criticisms) from its theological discourse and so this kind of dialogue is faintly heard if at all.